The 2022 bird flu outbreak will be the deadliest in recorded US history.

As of Monday, about 50.3 million birds have been lost, approaching the 50.5 million that died in the 2014-15 epidemic.

This year’s outbreak is already the most widespread, with 619 premises infected, making it the worst bird flu outbreak the country has ever seen.

At the same time, there are signs that the US is improving its performance against the disease since the last outbreak. This is important because the bird flu threat is not going away anytime soon.

The outbreak has affected all sectors of the poultry industry, but not evenly.

By November 8th, the U.S. had nearly 39 million egg-laying hens, 8 million turkeys, 2.6 million broilers, 270,000 ducks and 117,000 when deaths were just under 50 million. The backyard bird was lost.

Most of the birds were killed not because they were sick, but because of human wipeouts of infected farm poultry. Population reduction is used.

The large number of laying hen deaths — three-quarters of the birds lost — came from just 32 farms, or 5% of the facilities infected. Egg farms have the largest average flock size of any poultry production system, exceeding 1 million on infected farms.

In contrast, the infected 346 buildings were clusters of backyards. That is, pastured small farms that raise birds for sale, and sheds that homeowners keep for their personal use.

Due to the small flock size, backyard flocks accounted for only 0.2% of bird deaths, even though they represented almost 60% of infected premises.

The spike in backyard cases is a far cry from 2015, when only 21 such flocks were infected. That increase may be a result of the unusual virulence of today’s virus strains.

Most avian flu strains start out relatively benign, wild waterfowlAfter the disease is transmitted from wild birds to poultry, through crevices in poultry houses and tracked faeces, the virus can mutate and cause more serious illness and death.

That’s what happened in 2015, when the last big wave of highly pathogenic bird flu hit the United States.

But this year, the Eurasian H5N1 strain is starting to infect waterfowl as much as the disease mutated seven years ago. Current strains even kill wild birds that don’t normally show symptoms of avian flu. Said USDA veterinary researcher Mary Pantin-Jackwood at a conference in Maryland last month.

history lesson

Bird flu has killed 50 million people this year, matching only the 2015 epidemic.

Since the first recorded highly pathogenic outbreaks in the 1920s, the disease has surfaced mainly in one herd.

The only major outbreak in 1983-1984 killed 17 million birds, mostly in Pennsylvania.

The number of deaths from the first two documented outbreaks is unknown, but they were confined to live bird markets on the East Coast in 1924 and to New Jersey in 1927.

In fact, all outbreaks so far this year have been concentrated in one region of the country.of 2015most of the 232 infected facilities were in Iowa and Minnesota.

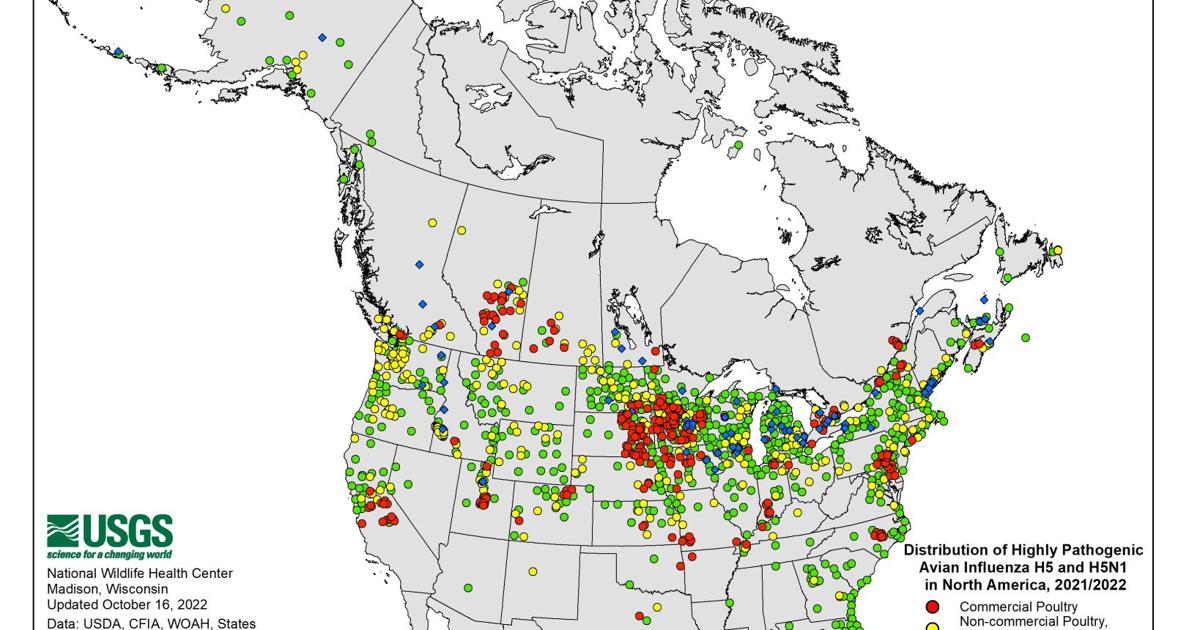

With 2.5 times more infected facilities, this year’s outbreak is essentially nationwide, affecting 46 states and all four of North America’s migratory bird flyways.

An infectious strain like this on the loose could definitely have made things worse.

Experts say the country’s bird flu response has been fine-tuned since 2015. Population decline is accelerating. Compensation payments to farmers have been simplified. Other countries have agreed to limit the geographic scope of trade restrictions.

In fact, the current outbreak is no worse than 2015, according to one efficiency indicator, the monetary cost of response.

The USDA Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service has so far contributed $567 million to combat the current outbreak, compared with more than $850 million in 2015.

This year’s cost is $348 million to compensate farmers whose birds and eggs were destroyed. $119 million for depopulation, disposal and virus removal. USDA spokesman Mike Stepien said he will spend $100 million in labor costs, state agreements and related costs.

It’s also worth noting that the US took longer to reach 50 million bird deaths than it did in 2015. Whereas the previous outbreak took him six months to finish, the current outbreak took him nine months to reach the same disastrous milestone.

The main reason for the low overall mortality is the high mortality on infected farms.

This year’s focus has been on rapid population decline, thus preventing the virus from multiplying in sick birds. The low viral load minimized the farm-to-farm transmission that was a problem in 2015. Said Julie Gauthier, Assistant Director of Poultry Health, USDA Veterinary Services, at a conference last month.

Regional difference

Still, not all poultry-producing regions in the country are equally affected.

As in 2015, the Midwest is being brutalized. Untouched Pennsylvania had 34 outbreaks in 2015. Hotspots also form in the Delmarva Peninsula, Utah, central California, and Alberta, Canada.

The Deep South, on the other hand, is mostly intact. Alabama and Louisiana have reported no poultry cases, and Georgia has reported only two chickens in her backyard flock. In Mississippi, the first infected farm was confirmed on November 5th.

It’s not that the region lacks poultry farming — it’s home to several major broiler states — or that the South doesn’t have wetland habitat.

In the case of Alabama, because Alabama is only between the main Atlantic route and the Mississippi flyway, fewer birds migrate through the state than its neighbors, said a poultry science professor at Auburn University. One Ken Macklin said:

Even with good biosecurity, the amount of time birds spend on farms can also be a risk factor, Macklin said.

A Southern specialty, broilers average just six weeks at home. Turkeys and laying hens, whose production is concentrated in the north, stay there for weeks or months or longer.

“The longer a bird stays in a poultry house, the more likely it is that a biosecurity breach will occur,” Macklin said.

The South may have also benefited from good timing – so far.

Macklin suspects bird flu wasn’t as prevalent among wild birds when they made their way north this spring.

When birds migrate south this fall, they may be carrying more viruses than they did in spring.

“I think we’re going to have multiple cases of HPAI in the southern states this winter,” said Macklin, referring to recent farm detections in Mississippi and three vulture pods in Alabama that tested positive. pointed out.

HPAI stands for Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza.

across borders

The current outbreak is historical, not just by American standards.

According to the European Center for Disease Prevention and Control, Europe has dealt with its own bird flu epidemic. This is the largest in the history of the continent.

By October 3, 48 million birds had been killed on about 2,500 farms. Like the United States, the disease has seen unprecedented geographic spread, hitting 37 countries from Portugal to Ukraine to the islands of Norway north of the Arctic Circle.

Earlier this month, the UK mandated that all poultry and farm birds be kept indoors due to an increase in bird flu cases.

Globally, 145 outbreaks involving 7 million commercial poultry were reported in 14 countries from September to mid-October.

Most cases occurred in deprived North America and Europe, but Algeria, South Africa and Taiwan were also affected, according to World Animal Health Organization.

The agency also said the virus had taken hold in wild birds more than previously known during the summer.

European experience also shows that avian influenza can rarely cross borders of another type – from birds to humans.

Two poultry farm workers in Guadalajara, Spain, contracted bird flu this fall, but there is no evidence that they have passed it on to others, the World Health Organization said on November 3.

In the United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention tracked the health of more than 5,000 people exposed to infected birds this year. Only one person was found to have bird flu in April while working to depopulate Colorado.

Avian influenza remains a low risk for the general population and is of greatest concern to sick birds and those exposed to virus-contaminated surfaces for long periods of time.

The CDC says workers in these situations should wear protective gear such as gloves and masks, avoid touching their mouths and noses, and change clothes after handling birds.

Even after this outbreak is over (it is not clear when that will be), bird flu will continue to pose a threat to both humans and animals.

After all, four influenza pandemics have hit humans since 1918, according to the CDC, and at least one, in 1968, involved strains with bird flu genes.

In a recent paper, Matthew Hayek, assistant professor of environmental studies at New York University, found that while the system could make poultry production more efficient, it also put thousands of birds in close proximity to allow the virus to spread and mutate rapidly. said it is possible.

Disease risks are also inherent in globalized food supply chains that move products quickly over long distances.

“A single incident or error in the value chain anywhere in the world could trigger a global pandemic,” a group of scientists said in a paper published this month by the Council for Agricultural Science and Technology. .

To protect birds during the current outbreak, animal health officials are urging that unwanted farm visitors be denied, other poultry owners excluded from farms, and clothing and shoes cleaned before and after entering poultry houses. Farmers are encouraged to disinfect.

Sick or dead birds should be reported promptly to the state agriculture department.You can find phone numbers to report in Mid-Atlantic states .