The advent of antibiotics turned many once life-threatening diseases into mild illnesses. Unfortunately, bacteria reproduce rapidly and adapt new gene sequences easily, making them well equipped to evolve resistance to lifesaving medicines, especially when antibiotics are overused or misused.

Infections with antimicrobial-resistant bacteria killed about 1.27 million people globally in 2019, according to the World Health Organization (WHO). Here, we take a look at the bacteria that WHO deems of critical or high priority. They cause lots of disease, particularly in low- to middle-income countries where health care resources are thin, and many are capable of transferring their genes to other bacteria. This means they can not only dodge antibiotics but also instruct other germs how to do so. These are the world’s 10 scariest superbugs.

Related: Dangerous ‘superbugs’ are a growing threat, and antibiotics can’t stop their rise. What can?

Carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii

Acinetobacter bacteria are found all over the place, but they are really only dangerous to humans in health care settings, where most of these infections begin. Of this group, Acinetobacter baumannii is the species that most often attacks humans, causing infections in the blood, urinary tract, lungs and wounds, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

The species is opportunistic, infecting people who have weakened immune systems or easy routes of entry for bacteria, such as catheters or surgical wounds. Acinetobacter strains have evolved different types of resistance.

The nastiest version is carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii (CRAB). CRAB has genes that make an enzyme called carbapenemase, which degrades a set of broad-spectrum antibiotics called carbapenems. Worse, according to the CDC, these genes are carried on highly mobile gene strands called plasmids, which bacteria can easily swap with one another, spreading their resistance abilities. Thus, the WHO ranks CRAB as a critical public health concern. A 2018 review found that the mortality rate from CRAB infections is 47%.

Third-generation cephalosporin-resistant and carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales

Also making the WHO’s critical list are two types of Enterobacterales bacteria: those resistant to cephalosporins and those resistant to carbapenems. Enterobacterales is an order of bacteria commonly found in the gut; Escherichia coli (E. coli) is one of the best known, but there are others, such as Klebsiella pneumoniae, a common cause of hospital-acquired pneumonia.

Like CRAB infections, Enterobacterales infections are typically associated with health care settings. The CDC estimates that Enterobacterales bacteria caused 13,100 infections and 1,100 deaths in hospital patients in 2017.

Of particular concern are third-generation cephalosporin-resistant Enterobacterales, which resist a group of antimicrobial compounds that had been a good option for treating bacteria with evolved resistance. The loss of third-generation cephalosporins to treat Enterobacterales infections also removes a tool for the treatment of brain infections caused by these germs, as the antibiotics can cross the blood-brain barrier.

Rifampicin-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infection of the lungs caused by the bacterium Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Ten million people contract TB each year, according to the WHO, and over a million die of it annually. These deaths are largely among the poor in regions where diagnosis and treatment are lacking; active TB can be cured with six months of treatment with four antimicrobial medications.

But some strains of tuberculosis are resistant to this regimen. Of particular concern, according to the WHO, is rifampicin-resistant TB. As of 2022, approximately 410,000 people each year contract a version of TB that’s resistant to rifampicin or to multiple antibiotics, according to the WHO. Doctors can try different combinations of medications for these difficult-to-treat, but treatment is more complex and often longer than regimens for non-drug-resistant TB. Because of the high disease burden from rifampicin-resistant TB, the WHO rates this microbe of critical concern, urgently requiring new antibiotics to combat it.

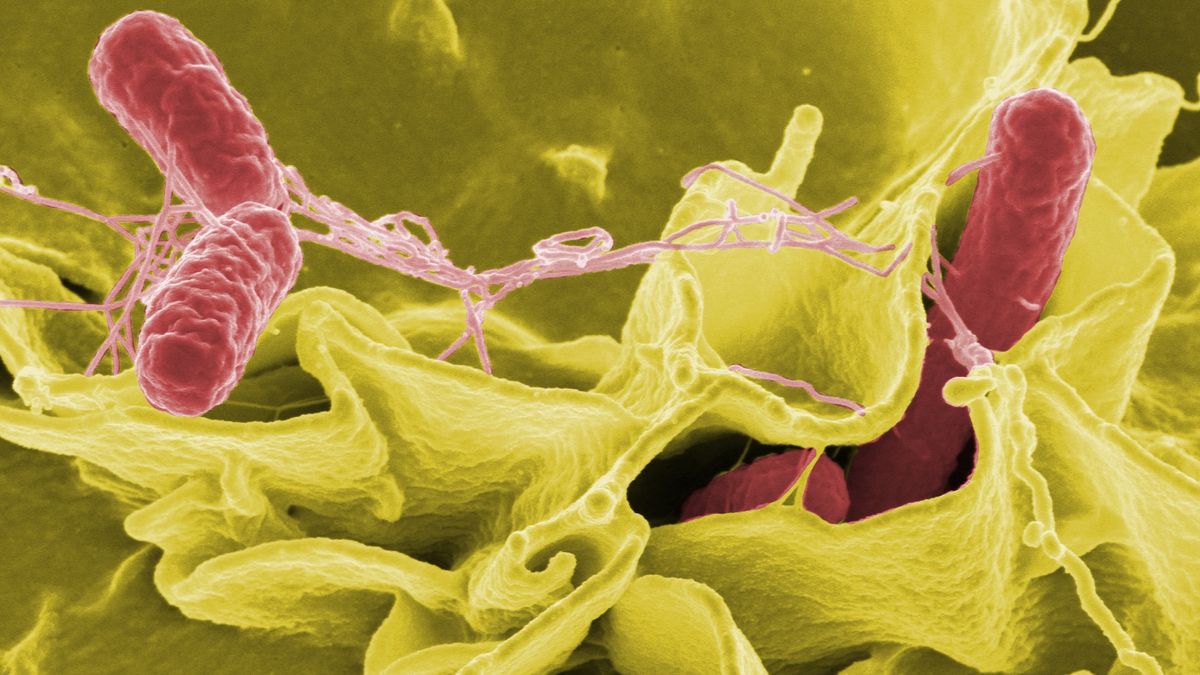

Fluoroquinolone-resistant Salmonella enterica Typhi

Salmonella enterica Typhi is the bacterium that causes typhoid fever, a serious gut infection that causes diarrhea, stomach pain, fever and headache. The WHO estimates that 110,000 people die of typhoid fever each year worldwide. The disease spreads through untreated water, and children are at the highest risk of dying from the infection. While typhoid fever is rare in the developed world, it is a grave concern in parts of Africa, the Eastern Mediterranean, and parts of Southeast Asia and the Western Pacific where sanitation and access to medical care is poor.

Typhoid fever was once easily treated with the antibiotics chloramphenicol, ampicillin and cotrimoxazole, according to the Coalition Against Typhoid. Unfortunately, in the 1970s, a multidrug-resistant strain emerged that could stand up against these first-line antibiotics. In response, doctors turned to fluoroquinolones, another class of antibiotics.

But over the past decade, doctors have increasingly reported illness that resists treatment with fluoroquinolones. In some regions, typhoid is now treatable only by one oral antibiotic, azithromycin, but there are concerns that the superbug is becoming resistant to that drug, too. According to the Coalition Against Typhoid, the best strategy is prevention: Hygiene, sanitation and typhoid vaccination can prevent the bacteria from getting a foothold.

Fluoroquinolone-resistant Shigella

Shigella is a genus of bacteria that cause gastrointestinal symptoms, including bloody diarrhea. These infections often clear up on their own, but the disease kills around 200,000 people a year, mostly in lower-income countries with poor sanitation, according to a 2023 paper in the journal Nature Reviews Microbiology. Young children, the immunocompromised, and older adults have the highest risk of death from Shigella infections.

Treating the infection in these at-risk groups has long been possible with antibiotics, but an alarming level of resistance is now emerging, according to the 2023 paper. From their perch in the gut, Shigella have the opportunity to mingle genes with numerous other bacterial species, and they’ve picked up genes to confer antibiotic resistance from these neighbors. Doctors are running out of antibiotic options, the authors of the paper wrote, and new drugs and vaccines are desperately needed.

Vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium

Enterococci bacteria are usually harmless in the human body, living in places such as the gut and the urinary tract. Sometimes, though, they grow out of whack or in the wrong place and cause infections. One of the most common friend-turned-enemy of the Enterococcus genus is Enterococcus faecium, which usually lives in the intestines but can sometimes infect the blood, the lining of the heart or the urinary tract, according to a 2018 review.

The antibiotic vancomycin is a go-to drug for these infections, but E. faecium is increasingly resistant. These resistant infections easily spread between immunocompromised patients at places such as hospitals and nursing homes, especially if proper sanitation practices are not followed, according to the New York State Department of Health. As is the case for many common hospital-acquired infections, this germ preys on older adults and patients with other health conditions.

Carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa

Pseudomonas aeruginosa likes moist places such as damp soil, and it can sometimes be found in bathtub drains and on human skin. Even in these cases, the bacteria do not necessarily cause disease. However, especially in patients with co-existing conditions, the presence of P. aeruginosa heralds worse health outcomes. It can also cause life-threatening infections on its own.

The WHO lists P. aeruginosa as a serious concern because it is increasingly resistant to carbapenems, antibiotics that are typically used to defend against bacteria that have resistance to other, front-line antibiotics. This resistance is particularly prevalent in South and Central America, according to a 2023 study in The Lancet: Microbe.

Fluoroquinolone-resistant non-typhoidal Salmonella

Not all Salmonella strains cause typhoid. Many of the 2,500 strains out there result in brief gastrointestinal symptoms, such as diarrhea. This is the kind of Salmonella that people sometimes get from undercooked or contaminated food.

Most people will recover from Salmonella infections without much treatment, and antibiotics are recommended only in cases when the bacteria escape the intestines and spread to other body systems, according to the CDC. But in a growing proportion of these “invasive” cases, doctors are finding that the bacterium is resistant to the first-line treatment, fluoroquinolones. As a backup, doctors sometimes use an antibiotic called ceftriaxone, a cephalosporin. Ceftriaxone resistance is rare, according to the CDC, but it is growing in some regions, particularly sub-Saharan Africa.

Third-generation cephalosporin- and/or fluoroquinolone-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae

Gonorrhea is one of the most common sexually transmitted infections, affecting more than 80 million people a year, according to the WHO. If untreated, it can cause infertility. Antibiotics almost always successfully treat these infections, which are caused by the bacterium Neisseria gonorrhoeae.

But over the past few decades, public health experts and doctors have noted increasing patterns of antibiotic resistance in gonorrhea cases. Resistance has been seen around the globe, with a 2022 study from Bulgaria finding that 59% of cases detected between 2018 and 2021 were resistant to the antibiotic fluoroquinolone. Some N. gonorrhoeae strains are now resistant to cephalosporins as well, leaving doctors fewer tools to combat this common infection.

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus

Colloquially known as MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus is a very common cause of antibiotic-resistant infections. About 1 in 3 people have S. aureus living harmlessly on their skin. If the bacteria grow out of control, however, infection can lead to swollen, pus-filled lesions and even progress to a life-threatening extreme immune response called sepsis and even death.

People who have breaks in their skin, such as surgery patients or those who use intravenous drugs, are at higher risk of contracting MRSA, according to the CDC, as are people who live or work in crowded conditions such as military barracks.

As of 2019, MRSA was the deadliest single antibiotic-resistant pathogen globally, according to a study published in the journal The Lancet, The resistant form of the germ alone caused more than 100,000 deaths that year alone.